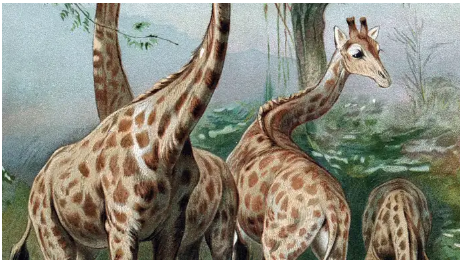

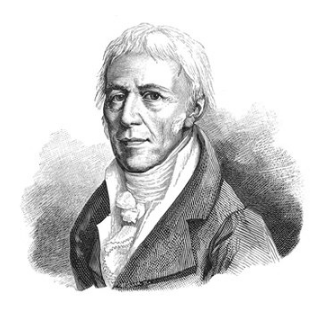

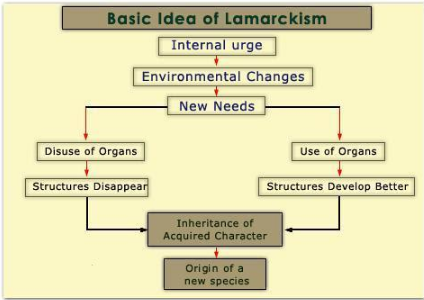

A theory of evolution based on the principle that physical changes in organisms acquired during their lifetime through use or disuse could be transmitted to their offspring is called Lamarckism, also known as Lamarckian inheritance or neo-Lamarckism.

It is also called the inheritance of acquired characteristics or more recently soft inheritance. The doctrine, proposed by the French naturalist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck (1744–1829) in 1809, shaped evolutionary thought through most of the 19th century. Lamarckism was discredited by most geneticists after the 1930s, but certain of its ideas continued to be held in the Soviet Union into the mid-20th century.

Experimentation

Experimental evidence for and against Lamarckism has come conspicuously to the front on several occasions. Such as:

- One line of evidence goes back to the extraordinary results of Charles-Édouard Brown-Séquard with guinea pigs. He believed that injury localized to one of the parents caused in the offspring epilepsy and sloughing off of a limb or toes. These effects he thought were sometimes transmitted to a few of the descendants. The results have not been confirmed by subsequent work. It became obvious that, unless work of this sort is done with inbred and pedigreed material, any conclusion is venturesome in the extreme.

- C. C. Guthrie exchanged the ovaries of black and white fowls and concluded that a change was brought about in them, but Charles Davenport’s later experiments showed that no such effects are produced. William Castle and J. C. Phillips transplanted the ovaries of a black guinea pig into a white one. When mated to a white male, black offspring resulted.

- John William Heslop-Harrison described the appearance of melanic forms in the moth Selenia after feeding on leaves treated with lead nitrate or manganese sulfate. The evidence pointed to the treatment that brought the change and that the change was directly on the germ cells. The melanic types that appeared, i.e, one dominant, the others recessive—were shown to give Mendelian inheritance when crossed to the type forms.

- Hermann J. Muller’s experiments with Drosophila treated with X-rays, in which defects, and even mutant types of a specific kind, were produced and inherited, appear to have been due to the direct action of the X-rays on the germ cells. Some of the mutant types thus produced were identical with those which had occurred spontaneously in earlier experiments. Radiation, heat, and certain chemicals are known to induce gene mutations. The effect is a direct one on the germ cells and not by way of somatic cells.

- The announcement by Ivan Pavlov in 1923 that a conditioned reflex established in mice is inherited and shows marked advances in each generation was withdrawn by Pavlov as an error. The results as announced were in direct contradiction to somewhat similar experiments by Halsey J. Bagg, E. Carleton MacDowell, and Emilia Vicari.

Eventually, the most complete disproof of the inheritance of somatic influence is demonstrated in almost every experiment in genetics. The facts here are positive and unquestioned and contradict thoroughly the claim that the germ cells are affected specifically by the bodily characteristics of the individual.

Perseverance of Lamarckism

By the 1930s the inheritance of acquired characteristics, i.e, the characteristic that has developed in the course of the life of an individual in the somatic or body cells, usually as a direct response to some external change in the environment or through the use or disuse of a part, had been rejected by most students of heredity, though belief in it persisted in popular and in some literary circles. Indeed, as late as 1955 British biologist Cyril Darlington called it the evergreen superstition. Lamarckism seems to be able to last indefinitely on the folklore level, but as a serious scientific hypothesis it has been abandoned. In about 1948 Lamarckism was revived rather violently by the Communist authorities in the U.S.S.R., and it became a part of the official biology.

Lamarckism in science

Lamarck had pictured the substantial characteristics, modified by an animal’s activities, as being passed onto future generations. Weismann showed that in animals the body and germ cells are separate, that only the germ cells produce the next generation, and that, consequently, all such modifications in the higher animals have to be transmitted from the soma of one generation to its germ plasm and then on to the soma of the succeeding generation.

Lamarckism

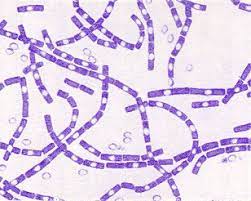

In unicellular organisms, where there is no separation of soma and germ plasm, Lamarckism, as it is understood in the higher forms, cannot apply. Induced changes in the germ plasm are known to be inheritable. Thus, in bacteria and protozoans, acquired modifications would be expected to be inherited. It was perhaps inevitable that this kind of inheritance would be cited by some as evidence of the inheritance of acquired characteristics. In the 1950s, spectacular advances in the genetics of bacteria and protozoa, the discovery of the importance of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) in the machinery of heredity, and the intensification of work on cytoplasmic inheritance made it essential that Lamarckism be understood accurately and precisely.

Sociocultural evolution

Within the field of cultural evolution, Lamarckism has been applied as a mechanism for dual inheritance theory. Gould ascertained culture as a Lamarckian process whereby older generations transmitted adaptive information to offspring via the concept of learning. In the history of technology, components of Lamarckism have been used to link cultural development to human evolution by considering technology as extensions of human anatomy.

3/01/2022